Working to Develop a More Safe and Convenient Treatment Option for Patients with Rare Platelet Disorder

While many people have heard of the blood disorder hemophilia, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a lesser-known bleeding disorder that also severely impacts patients’ quality of life.

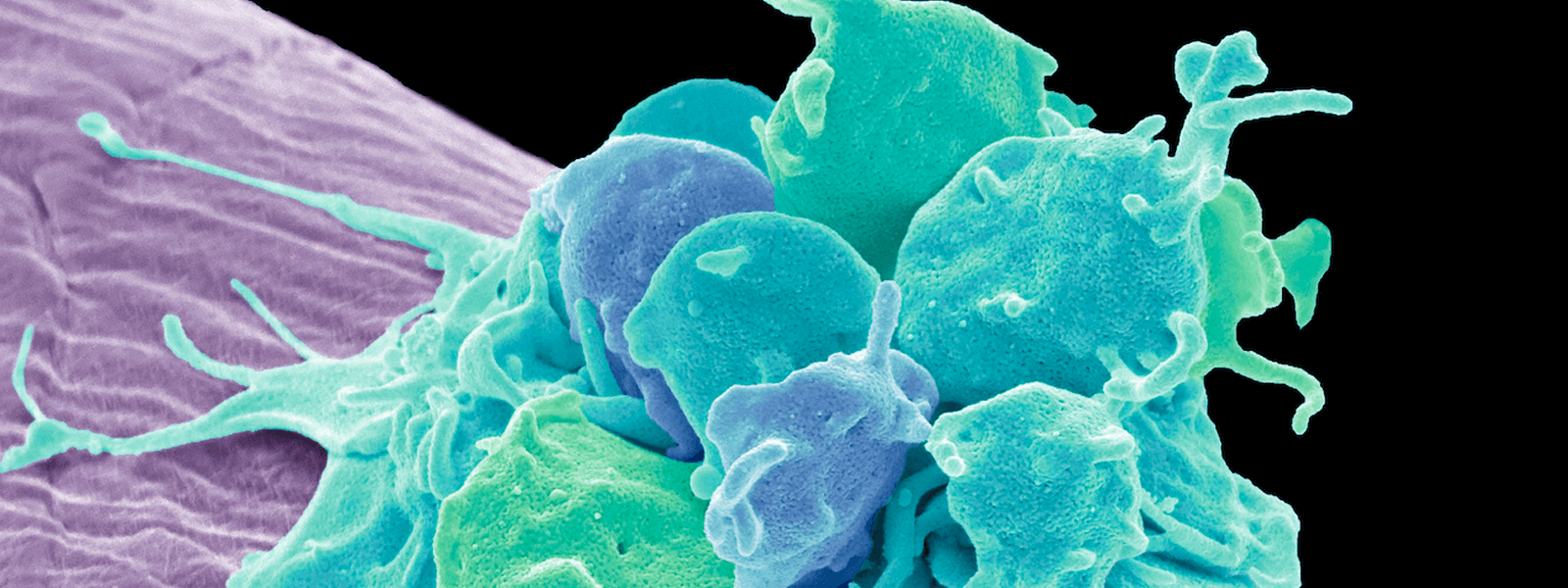

When you have a cut or injury, thrombocytes, or platelets, are tiny, colorless cell fragments that form a “plug” in blood vessels to help begin the clotting process. ITP is an autoimmune condition that causes a person’s immune system to attack their platelets, leading to low platelet counts. Some people with ITP may develop purplish bruises called purpura and have heavy nosebleeds and bleeding gums. Many suffer from constant fatigue and have to regularly monitor platelet counts in their blood.

ITP affects both children and adults. But it’s more common in children, who can develop the disorder after a viral infection, such as the flu or chickenpox. The majority of childhood cases spontaneously resolve.

In adults, ITP can be of shorter duration, but for many others it can become a chronic condition that has to be managed over a lifetime. An estimated 50,000 people in the U.S. are currently living with the condition.

Building a better therapy

One of the commonly used treatment options for ITP is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) a kind of “soup” of human antibodies. For patients who have low levels of platelets or who are about to undergo a surgery or medical procedure, IVIg is an emergency treatment used to help quickly increase platelet counts. It’s made from pooling together plasma from thousands of human blood donors and then purifying it.

But immunoglobulin, which is used to treat a variety of autoimmune conditions and other immune disorders, has a variety of drawbacks. It’s expensive and can be in short supply because it relies on human blood donations. Patients may have to sit for up to eight hours, sometimes over multiple days, to receive these infusions. And they can experience side effects such as nausea, rash, and migraines. There’s also a risk of infection or allergic reaction from these therapies.

With advances in gene technology, Pfizer researchers are working to develop a protein that mimics the effect of IVIg in autoimmune disorders and can be produced in the lab without relying on human blood products. The therapy uses recombinant protein technology to reproduce a small portion of the IVIg “soup” that has been shown to be most active in treating ITP, and other autoimmune conditions. Pfizer licensed the technology in 2013 from the Maryland biotech company Gliknik.

The recombinant protein could have a variety of benefits for patients. “It’s much easier to give because it's infused over a shorter period of time in a low volume,” says Lawrence Charnas, MD, PhD, Clinical Lead at the Rare Disease Research Unit at Pfizer. And because it’s not created from human blood product, there is no blood borne infectious risk.

The new potential therapy provides hope for patients, says Caroline Kruse, president and CEO of the Platelet Disorder Support Association. “For those suffering from ITP, the daily fear of experiencing a serious bleeding episode can be emotionally stressful and extremely difficult for both patients and their families. Combined with debilitating fatigue and depression, which is often underrecognized or not acknowledged, ITP has a huge impact on a person’s quality of life,” she adds.