Developing Potential Cancer Treatments to Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier

Every year, an estimated 200,000 patients with cancer in the U.S. are diagnosed with brain metastases¹ — or the spread of cancer cells from their original site to the brain — and when cancer spreads to the brain, it can become more deadly.2 Brain metastasis is more prevalent in certain cancers: between 10 and 30 percent of melanoma, lung, and breast cancers will metastasize to the brain.3

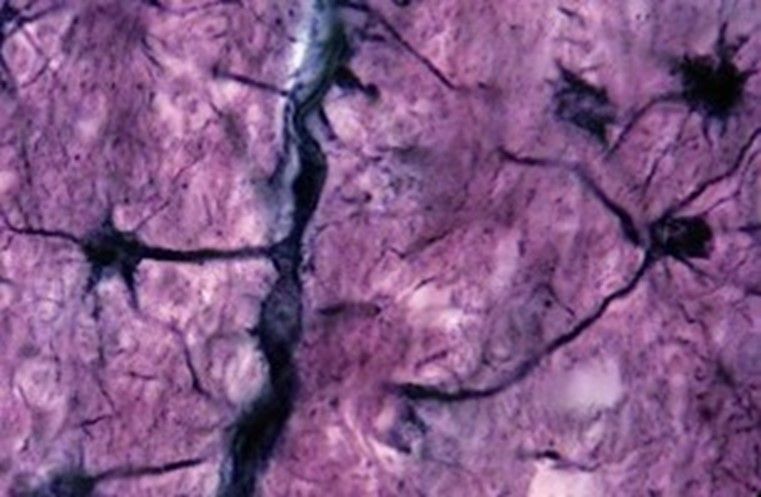

Many available cancer treatments have difficulty crossing over the blood-brain barrier, a tightly packed layer of cells that prevents toxins and other harmful substances from getting into the central nervous system, which consists of the brain and spinal cord. Though essential, this “security wall” for the brain can become an Achilles’ heel for some treatments — but our researchers are dedicated to identifying ways to beat this therapeutic challenge.

"Ultimately, it takes a team of people who are just so focused and determined to see their work impact patients."

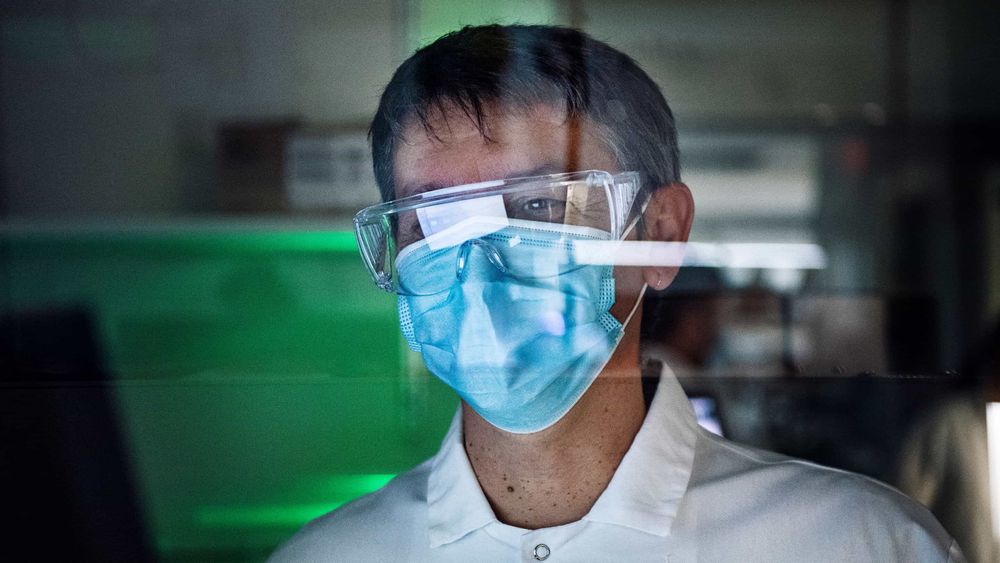

Our Research and Development site in Boulder, Colorado, includes a team of scientists working tirelessly to identify innovative molecules that may be able to safely and effectively cross the blood-brain barrier. Their mission is to develop next-generation targeted therapies that have the potential to not just penetrate the blood-brain barrier, but to remain there and more effectively treat cancer that has spread to the brain.

“It takes a mastery of chemistry, a mastery of 3-D structures, a mastery of a lot of sophisticated science and technology. But, ultimately, it takes a team of people who are just so focused and determined to see their work impact patients,” said S. Michael Rothenberg, M.D., Ph.D., Vice President and Head of Early Oncology Clinical Development at Pfizer Boulder Research and Development. “That’s what we have here in Boulder.”

The team has made progress on multiple fronts, including creating a “template” for brain penetrance — a set of characteristics that we believe every potential cancer-fighting molecule should possess to help it cross the blood-brain barrier.

Pfizer researchers are working diligently to discover how targeted therapies for cancer can cross the blood-brain barrier to treat cancer that spreads to the brain.

The team is also working to develop several potentially brain-penetrant molecules that target different gene mutations. One drug candidate currently being investigated for patients with a type of melanoma, known as BRAF-mutant melanoma, recently entered a Phase 1 clinical trial.

“Current BRAF inhibitors are limited by poor brain penetrance,” said Rothenberg. “Given that, we believe this molecule has the potential, if successful, to represent a significant advance over standard-of-care regimens in melanoma and other BRAF-driven cancers.”

In addition to our potentially first-in-class, brain-penetrant inhibitor in BRAF-driven cancers, the team is developing molecules that target genetic mutations known as cMET alterations, which have been found in lung cancer patients, and HER2 alterations, which are prevalent in both lung and breast cancers.

“Drugs that can effectively cross the blood-brain barrier have huge potential benefits, and we hope we will be able to bring additional treatment options to patients in need,” adds Dylan Hartley, Ph.D., Vice President, Boulder Research and Development.

National Cancer Institute. “Common Cancer Sites — Cancer Stat Facts.” https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html. Accessed November 24, 2021.

Hu J, Kesari S. Strategies for overcoming the blood–brain barrier for the treatment of brain metastases. CNS Oncol. 2013;2(1):87–98. doi: 10.2217/cns.12.37

Valiente M. et al. The Evolving Landscape of Brain Metastasis. Trends Cancer. 2018;4(3):176-196. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.01.003.