Early Detection is Key

In the fight against cancer, every screening, every result, every early detection matters. Join the fight against cancer and get screened at PfizerForAll.com/Screenings.

![]()

What is colorectal cancer? Learn more about the types, causes, risk factors, common symptoms, and available treatments for this disease.

In the fight against cancer, every screening, every result, every early detection matters. Join the fight against cancer and get screened at PfizerForAll.com/Screenings.

![]()

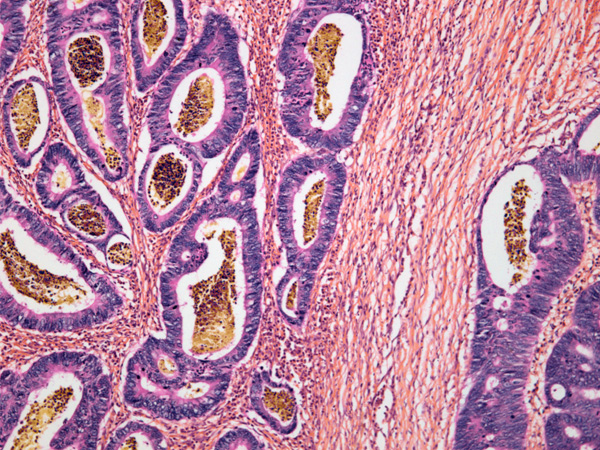

Colorectal cancer is a type of cancer that affects the colon, also known as the large intestine or large bowel, and the rectum, a portion of the large intestine that acts as a storage holder for waste.1,2 The colon and rectum are part of the digestive system, also known as the digestive tract—a system of organs that process foods for energy.2 Colorectal cancer starts when normal cells that line the colon or rectum begin to grow and change uncontrollably.3 These cells eventually form a tumor (which can be benign or malignant) in a process that takes years. Colorectal cancer is attributable to both genetic and environmental factors.4,7 While it’s still a leading cause of death for all genders, recent advancements in screening and therapeutics have improved survivability.5

In the U.S., the overall risk of developing colorectal cancer, including both colon cancer and rectal cancer, is about 1 in 24 for those assigned male at birth and 1 in 26 for those assigned female at birth. It’s the second leading cause of death in all genders and, excluding skin cancers, it’s the third most commonly diagnosed cancer.7

The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2024 there would be more than 106,000 new cases of colon cancer and over 46,000 new cases of rectal cancer.6 Thanks to improvements in screening for colorectal cancer, death rates from colorectal cancer have been declining in older adults for decades. Unfortunately, deaths from this cancer among people under the age of 55 (young onset colorectal cancer) have increased in recent years.5

Colorectal cancer is now the leading cause of death from cancer for those assigned male at birth aged 20-49 years, and the second-leading cause of death from cancer for those assigned female at birth aged 40-49 years.8

Survival rates can offer an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (such as 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t determine how long someone will live, but they may help to give a better understanding of how likely it is that treatment will be successful. The survival rate for colorectal cancer varies depending on the stage, ranging from 91 percent for localized cancers to 13 percent for distant ones. For rectal cancer, the rates range between 90 percent and 18 percent.48

Colorectal cancer is highly treatable and frequently curable when it's localized to the bowel. But recurrence after surgery is a significant problem.49

Most colorectal cancers are not hereditary, but a number of syndromes are associated with an increased risk of cancer. These include Lynch syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP).4

Often, colorectal cancer is slow-growing, beginning as a polyp.33,50 If left alone for many years, it can become cancerous. But early removal may stop this.34

Most often, polyps in the rectum and colon are not cancerous.50 Research demonstrates that as polyps increase in size, the likelihood of cancer increases.51

The lifetime risk for developing colorectal cancer is approximately 1 in 24 (4.2 percent) for those with people who were assigned male at birth and 1 in 26 (3.8 percent) for those assigned female at birth. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths for all genders.5

Colorectal cancers and polyps are frequently asymptomatic, especially early in their progression.30 When symptoms emerge, they may include changes in bowel habits, blood in stool, pain in the abdomen, unexplained weight loss, and iron deficiency.30,31 If you’re experiencing these symptoms, contact your primary care doctor, who may recommend tests or screenings.29 Something other than cancer may also cause these symptoms.30 The only way to know what’s causing them is to see your doctor.30

Patients and their doctors have several screening tests to choose from, including stool tests, a blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.34,35 Every test has pros and cons.34 Patients can talk to their doctors about which tests to take. Decisions will depend on preferences, medical conditions, available resources, and the likelihood a patient will complete a test.35

Once someone is diagnosed with colorectal cancer, there are multiple questions that need to be answered before a physician can determine colorectal cancer prognosis and treatment, options.41 Biomarker testing can also help you and your healthcare team decide which course of action is best for you.52 With this information, oncologists can take a more targeted approach to treating each case of colorectal cancer.39 More targeted treatments can lead to better treatment outcomes for people with colorectal cancer.40,41

Treatment for colorectal cancer typically depends on staging.41 In general, treatments involve a mix of surgery, medications, and therapies such as radiation. Your doctor will work with you to recommend the right course of treatment.41

Most colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. Some subtypes of adenocarcinomas may have a worse prognosis than others.3

Yes, but only for certain types of colorectal tumors. Immunotherapy is considered if a tumor has findings of dMMR (deficient mismatch repair) or MSI-H (microsatellite instability-high).44

Many drugs are approved for colorectal cancer treatment. Cancer.gov provides a list of drugs and drug combinations used for colorectal cancer and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.53

Typically starting with a polyp, colorectal cancer has a different name depending on whether it starts in the colon (colon cancer) or the rectum (rectal cancer).3

The types of colorectal cancers include:

Adenocarcinomas of the large intestine are a type of tumor that arises in the epithelial tissue of the colon or rectum.21 Over 90% of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas.3,7,8

Previously referred to as gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, these develop in specialized cells known as neuroendocrine cells.22

This is a rare type of colorectal cancer that starts in the lymphatic system. The most common variety is non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.23,24

These start from nerve cells in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract.25

These form in the muscles that guide waste through a person's digestive tract.26,27

These are extremely rare, accounting for fewer than 1 percent of all instances of colorectal cancer. Surgery is the typical treatment.28

An inherited disorder that may begin to affect people in their teenage years and result in the development of hundreds or even thousands of polyps in the colon and rectum.29

Colorectal cancers and polyps are frequently asymptomatic, especially early in their progression. When symptoms do emerge, they often show up as:30

Abdominal pain and bowel issues aren't the only symptoms that the disease presents. Iron deficiency, with or without anemia, has been found to be the most frequent hematological manifestation in patients with cancer, particularly colorectal cancer.31

Both genetics and the environment play a role in the development of colorectal cancer.7 Researchers have identified several contributing risk factors to colorectal cancer, but it's still not clear how exactly they work together to cause this type of cancer. Known risk factors for colorectal cancer include:4

It’s estimated that about 90 percent of colorectal cancers are linked to certain lifestyle factors, such as consuming a low-fiber and high-fat diet, alcohol consumption, and using tobacco, which may have occurred decades before a patient was diagnosed.5,6 Researchers recently linked dietary metabolites to a protective or procarcinogenic environment in the colon. This environment is modulated by a person's microbiome.6

Your risk for colorectal cancer may also increase if your doctor discovers adenomas, or benign tumors, during a screening colonoscopy.4

Colorectal cancers can be traced back to DNA mutations that turn off tumor suppressor genes or turn on oncogenes (genes that help tumor cells grow and survive).4 The development of colorectal cancer usually requires changes in multiple genes.4

About 70 percent of the time, these mutations are considered sporadic, meaning they occur without a family history of the disease.9 And 20-25 percent of the time, mutations are part of familial clustering, meaning colorectal cancer is occurring more frequently within a family than one would expect if looking at the rates of the disease in the general population.13,14 Finally, about 3-5 percent of the time, colorectal cancer is the product of an inherited syndrome.7

For example, some inherited syndromes associated with colorectal cancer include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), attenuated FAP (AFAP), Gardner syndrome, Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP).4

In many colorectal cancer cases, the first mutation shows up in the APC gene, which helps keep cell growth under control.4 This mutation leads to an increased growth of colorectal cells.4

Some groups have higher incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer, highlighting the need for targeted colorectal cancer prevention. Among the general population, African Americans have a notably high incidence of colorectal cancer—according to recent estimates, African Americans are about 20 percent more likely than people of other racial/ethnic groups to develop colorectal cancer. Unfortunately, African Americans are also about 40 percent more likely to die from the disease. Some of these differences are tied to a lack of access to screening, care, and other socioeconomic factors.11

Native Americans also experience higher incidence rates than non-Hispanic white populations—57.7 versus 41.3 per 100,000 in people who were assigned male at birth and 45.4 versus 32.8 per 100,000 in people who were assigned female at birth.12,13

Some people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage are also at a higher risk of developing colorectal cancers because of an inherited genetic mutation called APC I1307K.14

Colorectal cancer screening identifies early cancers and polyps (abnormal growths) in the large intestine, often leading to treatment before cancer can spread. Regular screenings are an effective way to reduce potential complications or death from colorectal cancer.18

Almost all colorectal cancers begin as precancerous polyps.18 These polyps are often asymptomatic and can be present for many years before cancer that is more invasive develops.19 Screening allows a doctor to find and remove polyps before they turn cancerous.19 According to the American Cancer Society guidelines for colorectal cancer screening tests, people at average risk of colorectal cancer should begin regular screenings at age 45.20 Screening for colorectal cancer is especially important for people with a family history of colorectal cancer, who may need to get a colonoscopy before age 45 or more frequently. Depending on a person’s health and life expectancy, the decision to be screened and the recommended frequency varies.20

While researchers are still investigating whether diet can reduce colorectal cancer risk factors, experts recommend a diet that is low in animal fats and high in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.19

Experts also recommend getting physical activity, limiting alcohol, and avoiding tobacco products to reduce the risk of developing colorectal cancer.19

Diagnosis of colorectal cancer often begins with a screening to evaluate whether symptoms or an abnormal test result may point to cancer. If a gastroenterologist suspects colorectal cancer, a biopsy may be recommended and then performed during a colonoscopy. During the colonoscopy, a doctor may remove a small sample of tissue with a tool that is passed through the scope. In less common cases, part of the colon might need to be surgically removed to make a diagnosis.38

Samples are then sent to the lab for examination.38 If cancer is found, other tests might be performed to more accurately classify the cancer and determine treatment options. Those tests may include biomarker testing, which examines genes, proteins, or other pieces of biological information that may provide more information about the type of cancer.38,39

For example, a doctor will likely order biomarker tests—such as for mutations of the genes KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF—to determine which drugs may be considered for treatment. A doctor might also order microsatellite instability (MSI) and mismatch repair (MMR) testing to determine whether certain treatments may be appropriate and to check for a possible connection with Lynch syndrome.38

These biomarkers provide clues as to how cancer develops. With this information, oncologists can take a more targeted approach to treating each case of colorectal cancer. More targeted treatments can lead to better treatment outcomes for people with colorectal cancer.38,39,40

If a polyp indicates a colorectal cancer diagnosis, a doctor might also send for additional imaging tests for colorectal cancer, such as a CT scan.38 The tests help determine colorectal cancer staging, which indicates how far the cancer has spread.38,41

Cancer at stage 0 has not yet grown beyond the inner cellular lining of the colon.41

Stage 1 cancer has grown deeper into the cellular layer lining the colon wall, but they have not spread beyond that.41

Stage 2 cancer has advanced through the colon wall. In some cases, it’s also spread to nearby tissue, although it has not yet spread to any lymph nodes.41

Stage 3 cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.41

Also known as metastatic colorectal cancer, stage 4 cancer has spread to distant organs, like the lungs or liver.41

Treatment for colorectal cancer will depend heavily on colon cancer staging. In general, treatments involve a mix of surgery, medication, and lifestyle adjustments.41

In this stage, since the cancer hasn't grown past the inner lining of the colon, polyps are surgically removed. This can often be done during a colonoscopy but surgery may be needed in certain cases.41

Treatment for this stage of cancer can involve removing a polyp. If the cancer has not spread to the edges of the removed tissue, it’s possible that no further treatment is required. If the polyp is high grade, or if cancer cells are found on the edge of the biopsy, then more surgery might be needed. Additional surgery might be required if the polyp couldn't be removed completely or if it was removed in multiple pieces.41

Cancers in this stage have often grown through the wall of the colon and possibly into nearby tissue. Removing the section of the colon along with lymph nodes nearby might be the only treatment necessary. A doctor might recommend testing for MSI or MMR gene changes to decide whether chemotherapy or immunotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) would be helpful. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is generally only recommended when colorectal tumors do not show MSI or MMR gene changes. In contrast, neoadjuvant immunotherapy is typically recommended when tumors have changes to MSI or MMR.41

In some cases, doctors might recommend chemotherapy after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) if they believe the cancer has a high risk of returning. This could be because:41

Doctors most often recommend a combination of chemotherapy medications if adjuvant chemotherapy is used.41,43

Since this stage involves cancers that have spread to lymph nodes, the standard treatment is surgery to remove the affected sections of the colon and lymph nodes, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens are most often a combination of two or three medications given at the same time.41

For advanced cancers that can't be removed with surgery, healthcare professionals may recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant immunotherapy to try to shrink the cancer, which could later make surgery possible.41

Doctors may recommend adjuvant radiation therapy when cancers that are removed with surgery are found to be attached to a nearby organ, or if they have positive margins (meaning some of the cancer may have been left behind).41

For people who aren’t healthy enough for surgery, or when a tumor’s location means a complete resection isn’t possible, doctors might recommend radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or chemoradiation (chemotherapy given along with radiation).41,42

At this stage, the cancer has spread to distant organs and tissues. Colorectal cancers spread most often to the liver. But they can also migrate to other areas, like the brain, lungs, distant lymph nodes, or the lining of the abdominal cavity. In these cases, colorectal cancer surgeries are unlikely to be curative. However, if the cancer has only metastasized to a few areas in the lungs or liver, surgery may extend life. Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer is often administered either before or after surgery.41

Research is informing a class of drugs that target specific changes in the cells responsible for colorectal cancer. A class of drugs that differs from chemotherapy (chemo), targeted therapies may be more effective than other forms of treatment for some people.43

Targeted therapies work on specific proteins that help cancer cells grow and spread. Some prevent the formation of blood vessels that feed the cancer, while others inhibit cancer growth. Physicians can prescribe targeted therapies alone or in conjunction with chemo. Side effects from the treatment drugs may differ depending on the treatment, but common side effects include fatigue, fever, diarrhea, nausea, and liver problems, among others.43

Biomarker testing can help identify appropriate targeted therapy options for a particular patient, given the presence or absence of certain genetic mutations in the tumor.3 Biomarker testing may also point to the presence of an aggressive disease or help predict disease prognosis.39,40

Some people who have colorectal cancer may benefit from immunotherapy, which triggers the body’s own immune system to fight cancer cells. Doctors may suggest immunotherapy depending on the presence or absence of certain genetic mutations in the tumor, such as the presence of deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H). The cancer’s stage also helps determine whether immunotherapy could be effective.41,44

Nutrition can be a powerful secondary tool in supporting cancer treatment options. Eating well may boost energy reserves and help the body fight against infection. Additionally, a good diet during cancer treatment may help to cope better with side effects or handle stronger doses of certain medicines.45

Trying some new foods during treatment might reveal that some things may taste better while receiving therapy. The American Cancer Society recommends experimenting with eating more plant-based foods and try to consume fruits and vegetables daily in a variety of colors. They also suggest trying to avoid processed foods, sugary drinks, and processed meats.45

Colorectal cancer complications can be serious. They include perforation of the colon, obstruction, and bleeding.32

As colorectal cancer progresses, it can cause bowel obstruction, can spread cancer to other tissues or organs (metastasis), and can develop into second primary colorectal cancer.33

According to the World Health Organization, colorectal cancers are a leading cause of death and illness across the globe.46 In the U.S., they made up 11.6 percent of all cancer treatment costs in 2020, the second highest for any cancer in the country.47

Colorectal cancers are estimated to be the third most common cancer and the second most deadly cancer, with an incidence of more than 1.9 million cases and just under 1 million deaths worldwide in 2020, which is the most recent data available. Incidence rates of colorectal cancer have been decreasing in high-income countries due in large part to screening programs, but there are still large geographical variations in incidence and mortality for the disease. The same statistics report notes that Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have the highest incidence rates of colorectal cancer, while Eastern Europe has the highest mortality rate. The number of new cases is projected to rise to 3.2 million per year by 2040.46

Thanks to advancements in colorectal cancer screening, it’s now possible to detect polyps and cancer earlier. This increases the likelihood of effective prevention and treatment.5

Currently, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for adults aged 45 to 75. After this age range, screening decisions are made on an individual basis. Patients should work with their doctors to determine when to start screening, which tests to take, and how to set up an ideal testing schedule.34

Patients and their doctors have several screening tests to choose from, including stool tests, a blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.34,35

Every test has pros and cons. Patients should talk to their doctors about which tests to take.35

This test involves the use of a long, thin, flexible tube with a light on it inserted into the patient’s rectum to check for both polyps and cancer in the rectum and colon. Doctors are able to remove most polyps and even some cancers during the screening. Colonoscopies can also be used as a follow-up test if a doctor finds anything unusual during other screening tests. Colonoscopies are generally performed every 10 years for anyone who does not have an increased risk of colorectal cancer.34

Stool tests come in four forms:34

In July 2024, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a blood test as a primary form of screening for people who have an average risk of colorectal cancer. This first-of-its-kind screening test looks for changes to free-floating DNA in the blood that can signal the presence of tumors or precancerous growths in the colon.35

Like colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy uses a thin, flexible tube and light. However, the shorter tube used with flexible sigmoidoscopy focuses only on the lower third of the colon. The tube is inserted into the patient's rectum to check for polyps or cancer. It's performed every five years, or every 10 years with a FIT each year.34

Also known as a virtual colonoscopy, this test uses X-rays and computers to examine the entire colon. The images are displayed on a computer for a doctor to review.34

Find a Pfizer clinical trial for colorectal cancer at PfizerClinicalTrials.com.

Explore colorectal cancer clinical trials at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Area of Focus: Oncology

Colorectal Cancer is a focus area for Pfizer Oncology. To learn more about how we’re accelerating breakthroughs to outdo cancer, visit the Oncology page.

Find resources for those living with cancer and their caregivers at This is Living with Cancer.

The information contained on this page is provided for your general information only. It is not intended as a substitute for seeking medical advice from a healthcare provider. Pfizer is not in the business of providing medical advice and does not engage in the practice of medicine. Pfizer under no circumstances recommends particular treatments for specific individuals and in all cases recommends consulting a physician or healthcare center before pursuing any course of treatment.

Related Articles

In the United States, an estimated 147,950 people were diagnosed with cancer of the colon or rectum in 2020. It is one of the most highly diagnosed cancers in the US, with 12 percent of cases diagnosed in people under the age of 50.[i] Additionally, more than 20 percent of Americans with colorectal...

If you’ve recently been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma or metastatic colorectal cancer, chances are you’ve had to familiarize yourself with a lot of new terms and complicated concepts. One term you may not have heard before is “biomarker.” As researchers learn more about how cancer cells...