How Maternal Immunization Works and Why It's Important for Your Child

The instinct to protect a baby starts when it's in the womb. Some of the most common ways a mother does this is through receiving regular prenatal care, taking prenatal vitamins, and prioritizing a healthy diet and rest. A less frequently discussed, but equally crucial, step that mothers-to-be can take is getting themselves vaccinated during pregnancy.

Even a brief look at the history of maternal immunization reveals that the antibodies provided by vaccination can be one of the greatest gifts a pregnant person can give their child. Over the past 200 years, scientists have documented the incredible impact vaccination has on fetal health—effects that extend from pregnancy through infancy, contributing to overall public health by helping babies fight diseases and grow strong.

The science is clear: Immunization helps support infant health. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that pregnant persons receive several vaccinations during pregnancy to help protect infants. Maternal immunization provides important protections in the first few months of life before infants are eligible to receive their first vaccines.1

The History of Vaccination During Pregnancy

The immunization of pregnant people has a long history. Maternal vaccines have led the way for improved mother and baby health since the 1800s.

Smallpox was reported to be more severe during pregnancy. An uncontrolled study found that vaccination during pregnancy helped protect infants against smallpox during the early part of their lives. In the 1940s, vaccination of mothers with whole-cell pertussis was shown to efficiently transfer antibodies to infants. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, vaccination against polio and influenza were recommended and broadly implemented to combat increased mortality in pregnant people and address the spread of polio.2

Still, safety of vaccines in pregnant people has always been a concern. It is difficult to establish a causal relationship between vaccines and adverse events in pregnancy or an infant ;3,4 however, modern surveillance systems like the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System exist to collect information and protect public health.

Understanding Maternal Immunization

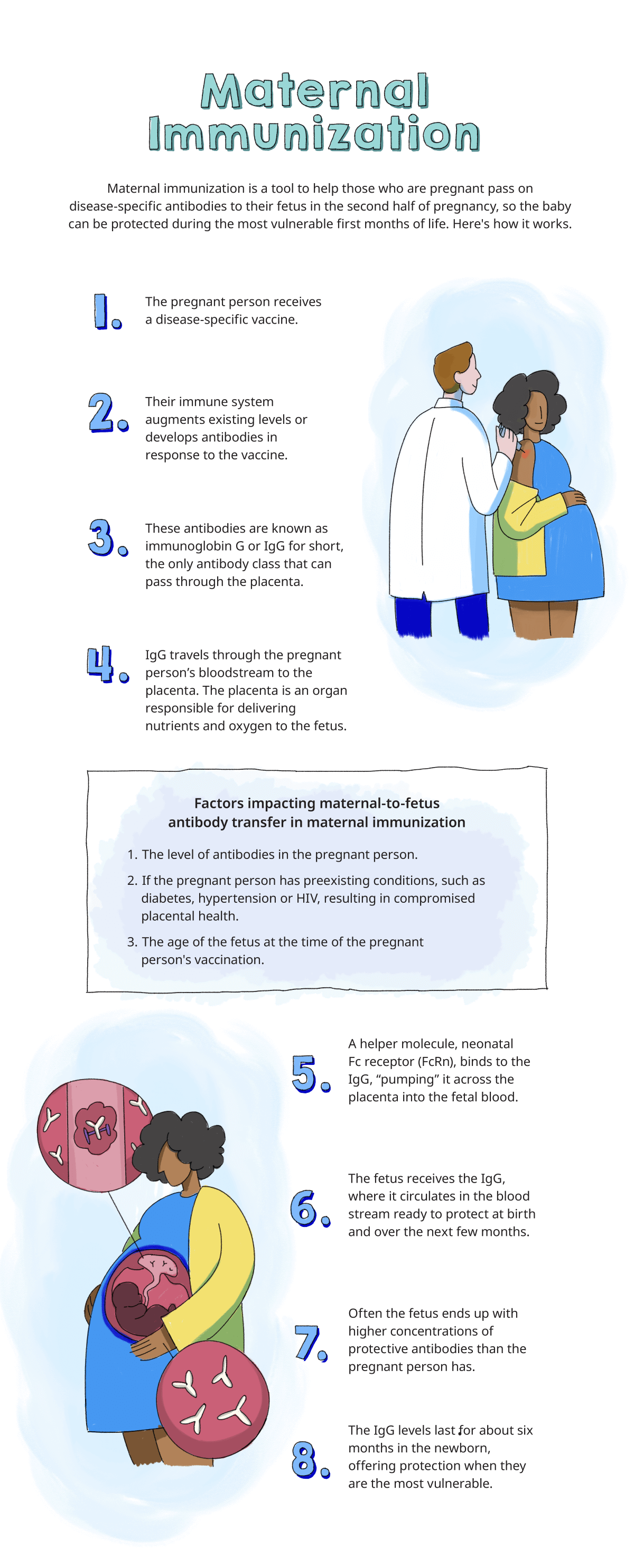

Maternal immunization takes advantage of the natural pregnancy process. Starting in the second trimester and peaking during the third trimester of pregnancy, antibodies (disease-fighting molecules) pass naturally from mother to baby through the placenta.3

Maternal antibodies protect infants against infections and vaccinations provide higher levels of those antibodies, providing even more protection when infants need it during the first few months of life before they are eligible to receive their first vaccines.3 Vaccines allow the pregnant parent to pass vaccine-induced maternal antibodies on to the child. The ability for vaccines to transfer passive protection to unborn children is the reason that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorses maternal immunization.4 The maternal immune system is activated when a pregnant person receives a vaccine. This elicits immunoglobin G (IgG) antibodies, which are passed through the placenta from the parental bloodstream and are secreted into the colostrum and milk that are transferred to the infant via breastfeeding.2,3

Maternal antibodies help protect the infant at birth and over the next few months. In fact, because of the way the placenta pumps antibodies into the fetus, fetal IgG concentration usually exceeds the concentration of antibodies in the maternal circulation in full-term infants.2 But the buildup of IgG protection in a fetus only happens if the pregnant person has the antibodies or the pregnant person is vaccinated during pregnancy. After birth, babies can continue to receive antibodies through breastmilk.3

"It's really an active process," says Kena A. Swanson, PhD, Vice President of Viral Vaccines, Vaccine Research and Development at Pfizer. "The placenta pumps the antibodies from a pregnant individual into the fetal bloodstream, so there can often be an even higher concentration of immune protection once the baby is born than is in the mother."

The Effectiveness of Maternal Immunization

The effectiveness and safety of maternal immunization have evolved steadily, with scientists around the world regularly contributing to the public's understanding. Today, for example, we know that the influenza vaccine is the most important protection against the flu.5 The shot protects both the pregnant parent and the baby from the virus, with studies of the vaccination showing the shot reduces a pregnant person's risk of hospitalization by 40%.2,6

The COVID-19 vaccine has a similar protective effect. When given during pregnancy, it boosts anti-spike IgG antibodies that can protect newborns and infants from the virus.7

Thanks to results like these, recommendations for maternal immunization have become widely accepted. These recommendations have been supported by long-term studies of the effects of vaccines on pregnancy, fetuses, and newborns. For years, health experts have routinely recommended maternal vaccinations, including the tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and influenza vaccines.1

The Future of Maternal Immunization

The science of immunization, and maternal immunization in particular, continues to progress. Scientists are gaining a deeper understanding of immunologic processes of typical pregnancies and the development process for new vaccines more often includes pregnant people.8

Conferences like The Fifth International Neonatal and Maternal Immunization Symposium are stepping into the future of maternal immunization by working toward the development of new vaccines, reviewing programs that are moving into clinical trials, and bridging the gap between immunization science and public health policy.9

Many research and development teams also recognize the importance of creating vaccines to specifically help improve the health of pregnant people and their infants. A particular focus for Pfizer is on development of maternal vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Group B streptococcus (GBS).

RSV is a common virus that usually causes mild symptoms, like a cold, in healthy adults but can cause potentially serious illness in young infants.10 GBS bacteria naturally occur in the human body11 but are a common cause of potentially severe infection in newborns when the bacteria enter the blood, lungs, or central nervous system, where it can cause sepsis, pneumonia or meningitis.12 Both RSV and GBS infection can be devastating for infants.

"RSV, for example, is responsible for more than 45,000 overall infant deaths annually, largely in developing countries, and is the leading cause of infant hospitalization in the developed world," says Swanson.

However, the future of maternal immunization is encouraging. In fact, Annaliesa Anderson, Senior Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer of Pfizer Vaccine Research and Development, believes that we are looking at a new horizon in maternal and child health.

"Recent data and analyses show that scientific acceptance and policy changes can provide new opportunities to prevent life-threatening infections in babies through maternal immunization, including for RSV and GBS" she says.

We hope to see healthier pregnancies, healthier babies, and improved public health as people better understand maternal vaccinations and take advantage of the resources available to them.