- Home

- Science

- Diseases & Conditions

- Sickle Cell Anemia

What Is Sickle Cell Anemia?

Sickle cell anemia, known medically as HbSS, is a type of inherited red blood cell disease. It is one of the most common among a group of inherited red blood cell disorders that are broadly labeled as sickle cell disease. People with sickle cell anemia inherit two sickle cell genes, one from each parent.1

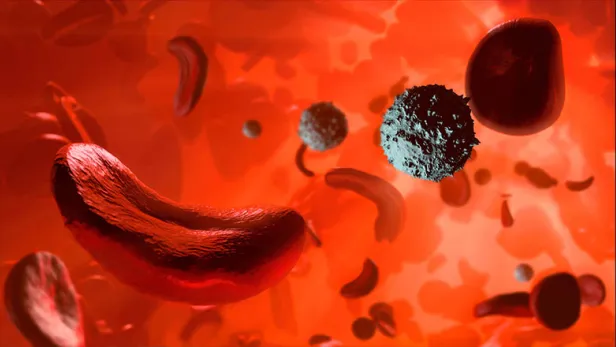

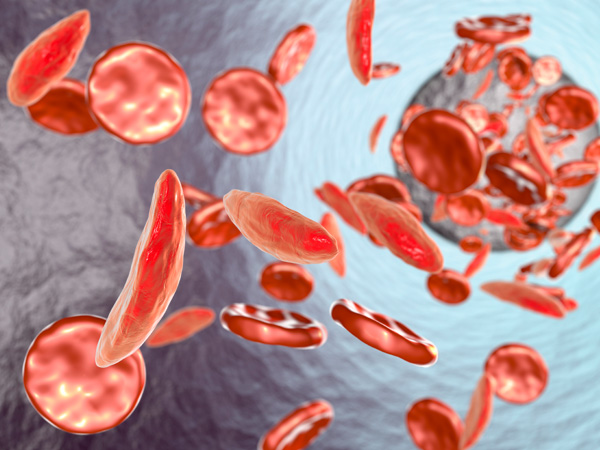

Red blood cells are typically flexible and round, allowing them to glide through blood vessels. In sickle cell anemia, blood cells take on a crescent moon or sickle shape. This problem stems from hemoglobin, a molecule that’s critical for transporting oxygen in the blood.2

In sickle cell anemia, hemoglobin is called hemoglobin S. This type of hemoglobin is caused by a mutation in the hemoglobin beta gene (HBB), which gives sickle cell hemoglobin its abnormal shape.1,3,4

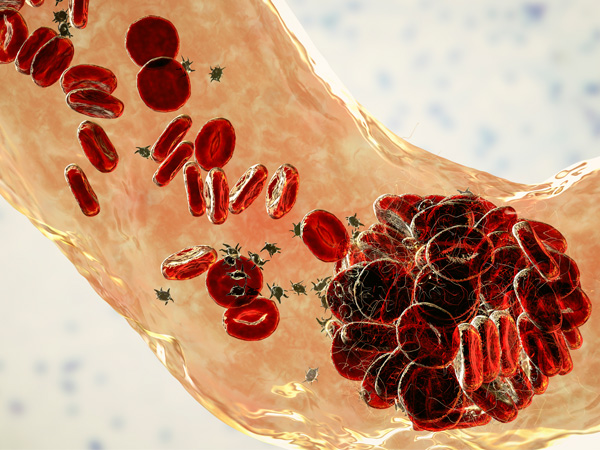

Human blood cells pass through body tissues, allowing those tissues to absorb most of the oxygen they carry.1 But rather than passing through smoothly like healthy blood cells, sickle cells become sticky and clump together, because sickle cell hemoglobin forms stiff protein rods inside the red blood cells. These bend the cells into their characteristic sickle or C shape.1,2,3

As these blood cells become rigid, they’re also more likely to burst or stick to each other, as well as other cells. This can obstruct blood flow.2,5

These obstructions can lead to intense periods of pain, called pain crises, which can last for hours or even days. These red blood cell changes can also cause another problem: anemia.2,5

Red blood cells typically have a lifespan of about 120 days before the body replaces them. Sickle cells, however, tend to have a 10-to-20-day lifespan. This can leave the body chronically short on red blood cells—a condition called anemia. Insufficient red blood cells leave the body oxygen-starved, which can lead to fatigue and can contribute to organ damage and dysfunction.1,5

Some treatment for anemia in people with HbSS can lead to high iron levels in the blood, which can damage organs.1

Children with sickle cell anemia sometimes experience splenic sequestration crises in the first decade of their lives. In a splenic sequestration crisis, the spleen becomes engorged with trapped blood, which lowers the amount of blood circulating elsewhere in the body, posing risk to the child.1,6,7

Over time, the spleen may shrink from these crises. But sometimes it doesn’t, requiring surgical removal of the spleen. This can lead to risks of infection.1,6,7

Prevalence of Sickle Cell Anemia

The precise number of people in the U.S. with sickle cell disease is difficult to pinpoint, but estimates range between 100,000 and 200,000.3,8 Sickle cell disease predominantly affects people with sub-Saharan African ancestry. It also occurs in people with Hispanic, South Asian, Southern European, and Middle Eastern ancestry.8 There are many types of sickle cell disease, but the most severe is sickle cell anemia.1

Sickle Cell Trait vs. Sickle Cell Disease

Having sickle cell trait does not mean you have sickle cell disease or, specifically, sickle cell anemia. With sickle cell trait, you inherit one sickle cell gene from one parent and a normal hemoglobin gene from your other parent.1 Approximately 1 in 13 Black people is born with sickle cell trait.1,8

The healthy hemoglobin in people with sickle cell trait functions well enough to prevent red blood cells from taking on the C shape. Consequently, people with sickle cell trait don't show any signs of sickle cell disease or anemia and can live normal lives. However, they can pass the gene on to their children. If two parents have sickle cell trait, each of their children has a 25% chance of inheriting sickle cell disease, which may include sickle cell anemia.9

Sickle Cell Anemia in Children

Sickle cell anemia is present at birth. Children will inherit the condition when they receive a sickle cell gene from each parent. Symptoms typically appear around 5 months of age.2

Causes and Risk Factors

What Causes Sickle Cell Anemia?

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic condition. It's recessive, which means the condition can only be inherited if someone receives a sickle cell gene —the gene with a sickle cell mutation—from both parents.2,3

A parent can pass on a mutated gene whether that parent has sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait. Children who inherit one defective hemoglobin gene and one healthy gene from their parents will have sickle cell trait, but they will be healthy.2

Despite its hereditary causes, several factors contribute to the severity and frequency of signs and symptoms of the disease, including infection, exercise, socioeconomics, air quality, and climate.10

Sickle Cell Anemia Risk Factors

Sickle cell anemia more often affects people who are Black or of Hispanic with Caribbean ancestry. For example, sickle cell disease affects about 1 of every 365 Black or African American children born in the U.S. and about 1 out of every 16,300 U.S.-born Hispanic children.8 The sickle cell gene, which is a known risk factor for sickle cell anemia, is more common in Black people and people whose ancestors came from areas like South America, the Caribbean, Central America, Saudi Arabia, India, and Mediterranean countries.8 If both parents have sickle cell trait—but not sickle cell disease, including anemia—a child has a 25% risk of inheriting the condition. However, if one parent has sickle cell trait and the other has sickle cell disease, the risk increases to 50%.11

Sickle Cell Anemia Detection

Certain tests can detect whether an unborn child has sickle cell disease. These tests, which are referred to as prenatal tests, include chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis. Both can determine whether a child will be a carrier of the trait or have the disease. Tests typically take place two to four months into a pregnancy.12

An early sickle cell disease diagnosis allows treatments to start sooner. And early treatments can reduce the frequency and severity of complications.2

Sickle Cell Anemia Symptoms

There are several symptoms that reflect sickle cell anemia. The severity and types of symptoms and complications affect life expectancy for people with sickle cell anemia. On average, people with sickle cell disease have a 54-year life span, which is much shorter than the 76-year life span typical of individuals without the disease.13 The median age at death for people with sickle cell anemia differs: 42 for those assigned male at birth and 48 for those assigned female at birth.2

In addition to fatigue, sickle cell anemia symptoms can include:

- Pain

Known as sickle cell pain crisis or vaso-occlusive sickle cell crisis, pain crisis occurs because the C-shaped red blood cells impede the flow of blood through the small blood vessels around the body, especially in, chest, abdomen, and limbs. Bone pain is also possible. Pain can appear suddenly and last for only a few days or for several weeks. The severity of pain can also vary; the most severe instances may require hospitalization. Pain frequency also differs by person. Some people have only a few sickle cell pain crises annually while others can have a dozen or more.2,14

- Frequent infections

Due to spleen damage, people with sickle cell anemia experience higher risk for developing infections. Infants and children with sickle cell anemia receive vaccinations and necessary antibiotics that can stave off infections, such as pneumonia, that can be life-threatening.2,3,6,7

- Vision impairment

Sickle cells can clog the small blood vessels that run through the eyes. This can lead to damage to the retina, the part of the eye that senses light and sends images to the brain. Sometimes, permanent vision problems can occur.15

- Swelling in hands and feet

Swelling occurs when sickle cells clog blood flow in the hands and feet.16

- Growth and puberty delays

Children with sickle cell anemia are sometimes smaller than children who do not have the disease. They also tend to start puberty later.17 One study found that in a group of children observed over 4 years, growth measured in body mass index, weight, or heigh declined in 84% of study participants.18

Sickle Cell Anemia Complications

Having sickle cell anemia increases the risk for several complications:

- Splenic sequestration crisis

Primarily affecting young children, splenic sequestration crisis occurs when blood becomes stuck in the spleen, lowering the overall amount of blood circulating throughout the body and causing painful swelling of the spleen. If untreated, the spleen can stop functioning, shrink, or become scarred.6,7

- Aplastic crisis

Aplastic crisis occurs when hemoglobin levels fall rapidly. Parvovirus B19 can trigger an aplastic crisis, along with other viral infections.19

- Hyperhemolytic crisis

Like aplastic crisis, hyperhemolytic crisis stems from a quick drop in hemoglobin levels. If untreated, it can cause organ failure and death. This rare complication can follow red blood cell transfusions.20,21

- Stroke

This potentially fatal complication can happen when the C-shaped sickle cells block major blood vessels in the brain, cutting off oxygen and causing severe damage. Weakness in the arms and legs, slurred speech, seizures, and loss of consciousness can indicate a stroke. Having one sickle cell stroke puts a person at greater risk for having more.16,22,23,24,25

- Acute chest syndrome

Acute chest syndrome is a serious lung-related complication occurring in patients with sickle cell disease or anemia. The syndrome is like pneumonia and is the leading cause of death and hospitalization in those with the disease.16,19

- Pulmonary hypertension

This potentially fatal complication happens when there is high blood pressure in the lungs. It makes you tired and breathless.16

- Priapism

Sickle cells can block blood vessels in the penis, creating long-lasting, painful erections that can lead to impotence if left untreated.16

- Sickle cell retinopathy

Caused by blocked blood flow to the retina and choroid (the layer of blood vessels between the retina and the white of the eye), this complication can occur in people with sickle cell disease, including those with sickle cell anemia, causing impaired vision or vision loss.15,26 There are two types of sickle cell retinopathy:

- Nonproliferative. Sickle cells block blood flow to the retina. This can cause the blood vessels to burst and create round lesions in the eye that usually heal with time.15,26

- Proliferative. Long-term oxygen deprivation and low blood flow cause the eye to grow new, irregular blood vessels that cause leaking behind the retina. Over time, blood can seep either in or behind the eye.15,26

- Gallstones

Bilirubin, produced as sickle cells break down, can accumulate and lead to gallstones, small hard masses that form in the gallbladder that can cause severe pain.16

- Leg ulcers

Open sores on the legs are more common in patients who are age 20 or over. While people with several kinds of sickle cell disease can develop leg ulcers, they often occur in patients with sickle cell anemia.27

- Organ damage

The C-shaped sickle cells can block blood flow to any number of organs, including the liver, spleen, and kidneys. Over time, consistently low oxygen levels in the organs can permanently damage organs and nerves. It can also be fatal.16

- Pregnancy complications

During pregnancy, sickle cells increase the risk for clots and high blood pressure. People who have sickle cell anemia also have a higher risk for premature birth, miscarriage, or babies with a low birth weight.28

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

The sickle cell shape makes the blood thicker, increasing the risk that a potentially fatal clot will form in the lungs or a vein. People with sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia, may experience deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.16,29

Diagnosis and Treatment

Sickle Cell Anemia Diagnosis

Sickle cell anemia is typically diagnosed with a blood test, which detects whether a person has the genetic underpinnings of the disease, as well as whether a person has abnormal hemoglobin.2,30

In adults, diagnosing sickle cell anemia involves collecting a blood sample. For children, sickle cell screening is part of the routine tests conducted on newborns. A small blood sample from the heel is enough to detect defective hemoglobin.2,30

If a patient receives a sickle cell anemia diagnosis, a doctor may recommend genetic counseling and additional tests to assess whether any other complications exist.2,30

Sickle Cell Anemia Treatments

A bone marrow transplant is the only available cure for some patients who have sickle cell anemia.2 Physicians will also use medicine to prevent blood cells from taking a sickle shape, reduce pain crises, and manage other complications.31

- Bone Marrow Transplant for Sickle Cell Anemia

This procedure is currently the only sickle cell anemia cure. It's not readily available to all patients due to its high cost and the need for a good donor-patient match. In this procedure, the patient's bone marrow stem cells are replaced with non-sickle stem cells from a donor. With a successful procedure, production of sickle red blood cells is replaced by production of normal red blood cells. Because the procedure carries risks, it's typically reserved for patients experiencing many sickle cell anemia complications.32

- Sickle Cell Anemia Medication

Antibiotics are suggested to reduce the risk of infection common in many people with sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia.2 People with sickle cell crisis may be prescribed antimetabolites.33,34 Antimetabolites are sometimes used to treat sickle cell anemia because of their ability to disrupt the formation of new cells.35 Antimetabolites may increase the level of hemoglobin F (fetal hemoglobin), the fetal form of the main oxygen-carrying protein in blood. Fetal hemoglobin can interfere with the sickling process. Antimetabolites also reduce the number of leukocytes (a type of immune cell) and increase nitric oxide levels in the blood, which could improve blood flow.33,34 An intravenous medication is also available that can prevent blood cells from sticking to blood vessel walls, reducing the risk of painful sickle cell crisis.37,38

- Transfusion for Sickle Cell Anemia

Transfusions are another treatment option for people with sickle cell anemia. A physician and healthcare team will remove and replace a patient’s blood, using one or more thin tubes called catheters, which they place into blood vessels. The patient’s blood is replaced with donor blood.31,39

Transfusions can reduce the number of complications that sickle cell anemia patients face. Some of those complications include pain crisis and acute chest syndrome. Transfusions may also be useful for preventing strokes in patients with sickle cell anemia.31,39

Transfusions are not without risks. They can trigger pain crises, shock, or issues with the lungs. This is because transfusions can increase the thickness of the blood.39,40

- Lifestyle Changes for Sickle Cell Anemia

In addition to medical treatments, patients can make changes in their daily life that may reduce the impact of sickle cell disease and anemia.41 Some strategies are:

- Drinking 8-10 glasses of water daily41

- Rest during a sickle cell crisis42

- Avoiding extreme exercise3

- Eating a balanced diet44

- Limiting emotional and physical stress45

- Taking folic acid46

Global Impact of Sickle Cell Anemia

While estimates vary, sickle cell anemia disease affects more than 300,000 newborns worldwide each year.47 Lack of access to early diagnosis and treatment for sickle cell anemia causes at least 500 deaths among children daily. About 238,000 sickle cell anemia births occur in sub-Saharan Africa and more than 46,000 occur in India each year.48

In the United States, researchers have estimated that each year, people with sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia, lose a total of $3,145,862 in wages, due to missed work. Their caregivers lose $2,870,652 in total.49 On average, a U.S. patient with sickle cell disease accumulates $12,691 annually in healthcare costs.50 The price tag carries an equally heavy burden in Africa, where treatment per episode can cost the equivalent of two-thirds of a minimum wage salary.51

Although sickle cell anemia’s precise economic effects remain unclear, a study found that anemia exacerbation was the most expensive cause of emergency department visits among patients with sickle cell disease in Brazil. On average, each visit cost $321.87.52

Frequently Asked Questions About Sickle Cell Anemia

- Is sickle cell anemia dominant or recessive?

Sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia, is a recessive condition. To inherit the disease, a child must receive two copies of the gene for defective hemoglobin—one from each parent.2,53 If each parent only has one of the recessive genes, the child has a 25% chance of developing sickle cell disease and potentially sickle cell anemia. If one parent has a single trait and the second parent has sickle cell disease, the child's risk increases to 50%.11

- What races can get sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia?

Sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia, primarily affects people of African descent, including Black Americans. Individuals with Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian, and Mediterranean ancestry are also frequently affected, though the disease may occur in other ethnicities.8

- What type of mutation causes sickle cell anemia?

A mutation of the body's hemoglobin beta gene is responsible for sickle cell disease, including sickle cell anemia.54 The variation causes the hemoglobin to stiffen and take on a rod shape. That forces red blood cells into a crescent shape, like a sickle farm tool. Instead of blood flowing freely, red blood cells stick together and clog small blood vessels.54

- How common is sickle cell anemia?

It’s estimated that sickle cell anemia affects more than 300,000 newborns worldwide each year.46 The precise number of people in the U.S. with sickle cell disease and sickle cell anemia is unknown. Estimates range from 100,000 to 200,000.3,8 Data indicate 1 in 365 Black American babies will develop sickle cell disease, and 1 in 13 will have sickle cell trait. Additionally, 1 in 16,300 Hispanic American babies will develop sickle cell disease.8

- Is sickle cell anemia or sickle cell disease contagious?

No, sickle cell anemia and sickle cell disease are genetic disorders. They cannot pass between individuals except through inheritance.2

Learn More About Sickle Cell Anemia

Find a Pfizer clinical trial for Sickle Cell Disease at PfizerClinicalTrials.com.

Explore sickle cell disease clinical trials at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Area of Focus: Rare Disease

Sickle Cell Anemia is a focus of Pfizer’s Rare Disease Therapeutic Area. Visit the Rare Disease Page.

- References

- What is sickle cell disease? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/facts.html. Last reviewed December 14, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle cell disease. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/sicklecelldisease.html. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle cell anemia. About the disease. NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8614/sickle-cell-anemia. Last reviewed Nov. 8, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- HBB gene. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/hbb/#conditions. Last reviewed July 1, 2020. Accessed November 7, 2022.

- What Is Sickle Cell Disease? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/sickle-cell-disease. Updated July 22, 2022. Accessed Oct. 18, 2022.4. Last reviewed November 9, 2021. Accessed August 11, 2022.

- Kane I, Kumar A, Atalla E, Nagalli S. Splenic Sequestration Crisis. StatPearls. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553164/. Last reviewed June 8, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Al-Salem AH. Splenic complications of sickle cell anemia and the role of splenectomy. ISRN Hematology. 2011;2011:1-7.

- Data and statistics on sickle cell disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Last reviewed December 16, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle cell disease. Causes and risk factors. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sickle-cell-disease/causes. Last reviewed March 24, 2022. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- Tewari S, Brousse V, Piel F, et al. Environmental determinants of severity in sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2015 Sep; 100(9): 1108–1116. Published September 2015. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Introduction to the inheritance of sickle cell anemia. Sickle Cell Society. https://www.sicklecellsociety.org/resource/inheritance-sickle-cell-anaemia/. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle cell disease and pregnancy. March of Dimes. https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/pregnancy/sickle-cell-disease-and-pregnancy. Reviewed January 2013. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Lubeck D, Agodoa I, Bhakta N, et al. Estimated life expectancy and income of patients with sickle cell disease compared with those without sickle cell disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915374. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2755485. Published November 15, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Yale SH, Nagib N, Guthrie T. Approach to vaso-occlussive crisis in adults with sickle cell disease. AFP. 2000;61(5):1349-1356. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2000/0301/p1349.html. Published March 1, 2000. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle Cell Retinopathy. The Foundation of the American Society of Retina Specialists. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/41/sickle-cell-retinopathy. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Complications of sickle cell disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/complications.html. Last reviewed May 10, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022.

- Rhodes M, Akohoue SA, Shankar SM, et al. Growth patterns in children with sickle cell anemia during puberty: Growth in Sickle Cell Anemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(4):635-641.

- Zemel BS, Kawchak DA, Ohene-Frempong K, Schall JI, Stallings VA. Effects of delayed pubertal development, nutritional status, and disease severity on longitudinal patterns of growth failure in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(5, Part 1):607-613.

- Sickle Cell Crisis. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526064/. Updated August 29, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Trivedi, K, Abbas A, Kazmi R, et al. Hyperhemolytic Crisis Following Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease With Acute Hepatic Crisis: A Case Report. Cureus. 14(8): e27844. Published August 10, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Srinivasan A, Gourishankar A. A differential approach to an uncommon case of acute anemia in a child with sickle cell disease. Global Pediatric Health. 2019;6:2333794X1984867.

- Stroke signs and symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/signs_symptoms.htm. Last reviewed May 4, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Stroke symptoms. American Stroke Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-symptoms. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Controlling post stroke seizures. American Stroke Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/effects-of-stroke/physical-effects-of-stroke/physical-impact/controlling-post-stroke-seizures. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Syncope. American Stroke Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/health-topics/arrhythmia/symptoms-diagnosis--monitoring-of-arrhythmia/syncope-fainting. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Sickle cell retinopathy. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Sickle_Cell_Retinopathy. Last reviewed November 14, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Monfort JB, Senet P. Leg ulcers in sickle-cell disease: Treatment update. Advances in Wound Care. 2020;9(6):348-356. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7155924/. Published June 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Smith-Whitley, K. Complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2019 Dec 6; 2019(1): 359-366. Published December 6, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Noubiap JJ, Temgoua MN, Tankeu R, et al. Sickle cell disease, sickle trait and the risk for venous thromboembolism: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Thrombosis Journal. 2018;16(27). https://thrombosisjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12959-018-0179-z. Published October 4, 2018. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle Cell Disease Diagnosis. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sickle-cell-disease/diagnosis. Updated July 15, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle Cell Disease Treatment. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sickle-cell-disease/treatment. Updated July 15, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Ashorobi D, Bhatt R. Bone marrow transplantation in sickle cell disease. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538515/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538515/. Last updated July 12, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Hydroxyurea for Sickle Cell Disease: Treatment Information from the American Society of Hematology. American Society of Hematology. https://www.hematology.org/-/media/Hematology/Files/Education/Hydroxyurea-Booklet.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Mack A, Kato G. Sickle cell disease and nitric oxide: A paradigm shift? The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2006 Feb 17. 38(8): 1237—1243. Published February 2006. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Hydroxyurea. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a682004.html. Last Updated October 15, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2022.

- AlDallal SM. Voxelotor: A ray of hope for sickle disease. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32257653/. Published February 26, 2020. Accessed February 13, 2022.

- Crizanlizumab – a simple guide. Sickle Cell Society. https://sicklecellsociety.org/crizanlizumab. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- Riley TR, Boss A, McClain D, Riley TT. Review of medication therapy for the prevention of sickle cell crisis. P T. 2018;43(7):417-437.

- Exchange transfusion. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002923.htm. Last updated February 4, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2022.

- Vichinsky EP. Current issues with blood transfusions in sickle cell disease. Seminars in Hematology. 2001;38:14-22.

- Living Well with Sickle Cell Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/healthyliving-living-well.html. Updated December 16, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Practical tips for preventing a sickle cell crisis. American Family Physician. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2000/0301/p1363.html. Updated March 1, 2000. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- Light-to-moderate exercise may bring benefits for sickle cell disease. American Society of Hematology. https://www.hematology.org/newsroom/press-releases/2019/light-moderate-exercise-may-bring-benefits-for-sickle-cell-disease. Updated November 19, 2019. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- Moore M, Klemm S. Nutrition for the child with sickle cell anemia. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://www.eatright.org/health/allergies-and-intolerances/food-intolerances-and-sensitivities/nutrition-for-the-child-with-sickle-cell-anemia. Updated October 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- Shah P, Khaleel M, Thuptimdang W, et al. Mental stress causes vasoconstriction in subjects with sickle cell disease and in normal controls. Haematologica. 2020;105(1):83-90.

- Dixit R, Nettem S, Madan SS, et al. Folate supplementation in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online February 16, 2016.

- Royal CDM, Babyak M, Shah N, et al. Sickle cell disease is a global prototype for integrative research and healthcare. Advanced Genetics. 2021;2(1):e10037. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ggn2.10037. Published March 2021. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- McGann, P. Time to Invest in Sickle Cell Anemia as a Global Health Priority. Pediatrics. 2016 Jun; 137(6): e20160348. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4894249/. Published June 2016. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Holdford D, Vendetti N, Sop DM, et al. Indirect economic burden of sickle cell disease. Economic Evaluation. 2021;24(8):1095-1101. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S109830152101490X. Published August 1, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Shah N, Bhor M, Xie L, et al. Medical resource use and costs of treating sickle cell-related vaso-occlusive crisis episodes: A retrospective claims study. Journal of Health Economics and Outcomes Research. 2020;7(1):52-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7343342/. Published June 15, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Ngolet LO, Engoba MM, Kocko I, et al. Sickle-cell disease healthcare cost in Africa: Experience of the Congo. Anemia. 2016. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/anemia/2016/2046535/. Published February 2, 2016. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Lobo C, Moura P, Fidlarcyzk D, et. Al. Cost analysis of acute care resource utilization among individuals with sickle cell disease in a middle-income country. BMC Health Services Research. 22, 42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07461-6. Published January 8, 2016. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- Sickle cell disease: Inheritance. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/sickle-cell-disease/#inheritance. Updated July 2020. Accessed October 18, 2022.

- About Sickle Cell Disease. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Sickle-Cell-Disease. Accessed October 18, 2022.

The information contained on this page is provided for your general information only. It is not intended as a substitute for seeking medical advice from a healthcare provider. Pfizer is not in the business of providing medical advice and does not engage in the practice of medicine. Pfizer under no circumstances recommends particular treatments for specific individuals and in all cases recommends consulting a physician or healthcare center before pursuing any course of treatment.