Mending Broken Walls: 5 Insights About Gut Health Helping IBD Patients

Our skin is the most visible barrier that separates our bodies from the outside world. But deep inside the body, we have another critical wall, the gut epithelial barrier, which helps to block pathogens and toxins, while selectively allowing nutrients and water to be absorbed.

“The gut is a very exciting and dynamic kind of barrier,” says Marion Kasaian, Head of Epithelial Biology based at Pfizer’s Kendall Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts research site. “It has a larger surface area than skin and lung epithelial barriers and protects us from trillions of bacteria.”

Due to a variety of reasons, this barrier can sometimes become damaged. In recent years, scientists have begun to uncover how issues with epithelial barrier function can fuel chronic inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Current IBD treatments target the immune system and inflammation in the gut, but scientists hope that epithelial barrier research can drive the discovery of new targets and treatment options. “There are a lot of different ways that we can help to restore the barrier that we think will maintain the health of the gut in patients with IBD,” says Kasaian.

Advances in cellular models and systems, such as organoids and organ-on-a-chip, are helping scientists unravel how the epithelial barrier functions and responds to treatments. “It’s really a very transformative time to be looking at epithelial cells,” says Kasaian. “We can do a lot more now than ever before.”

Read on to learn some key insights into the gut barrier and its link to IBD.

1) The gut barrier is a self-repairing wall.

It consists of a single layer of epithelial cells that is constantly going through cycles of damage, repair and renewal. Inflammation is necessary for wound healing. But if there’s too much inflammation, there can be tissue damage and increased exposure to microbes, which can further escalate the inflammatory cascade. When these repair mechanisms are dysregulated in genetically-susceptible individuals, chronic inflammatory conditions can drive the onset and progression of IBD.

2) It’s more than a “physical” barrier keeping pathogens out.

“It’s also a chemical barrier,” says Michelle Rooks, a Senior Principal Scientist in the Inflammation and Immunology Research Unit, also based at Pfizer’s Kendall Square Research Site. The epithelial cells produce a variety of molecules that are key to maintaining barrier balance and help our immune system mount appropriate reactions to resident gut microbes.

3) Cellular “self-eating” is critical to maintaining the barrier.

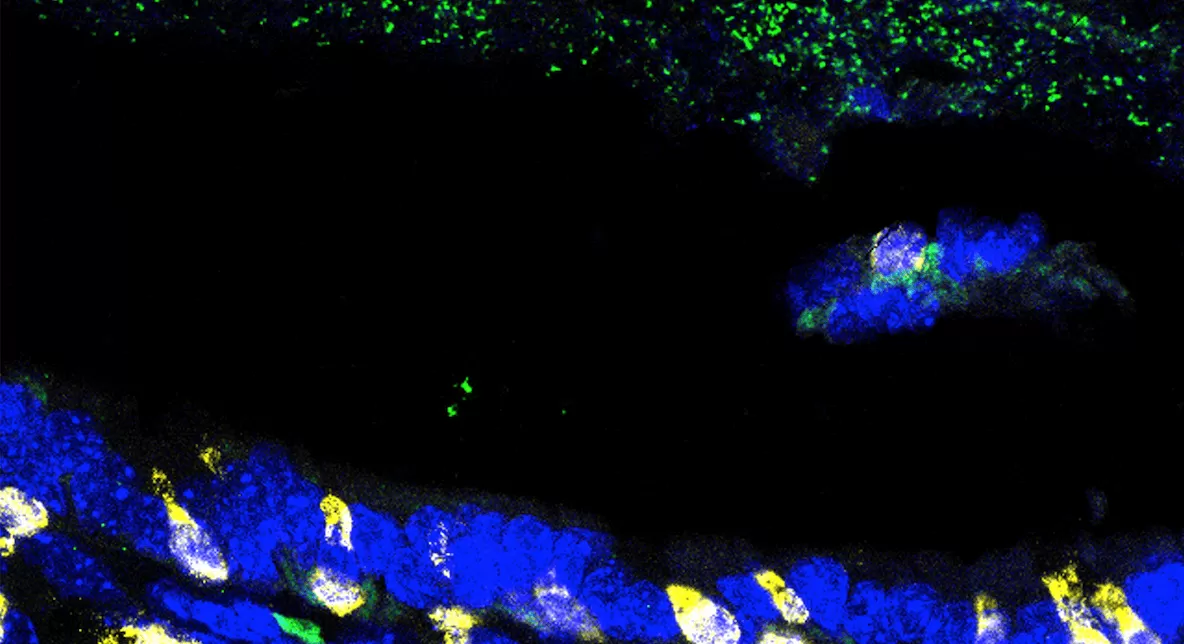

In a healthy gut, the epithelial barrier undergoes autophagy, or cellular self-eating, to recycle intracellular components, clear bacteria and maintain the mucus layer. Genetic data shows there may be problems with this process in patients with IBD. “We’re interested in exploring the link between autophagy defects and IBD to understand how it regulates intestinal barrier function,” says Rooks.

4) The “mortar” holding the wall together is a key component, too.

Each epithelial cell that forms the gut wall interacts with neighboring epithelial cells through connections called “tight junctions.” These intracellular connections regulate the movement of water and other materials through the wall. If there is a breakdown in tight junctions, the gut is more permeable allowing potentially harmful materials to pass through. Scientists are exploring ways to fortify these tight junctions. “We are interested in setting up models to study tight junctions and test approaches for maintaining barrier integrity,” says Rooks. “A few years ago, we didn’t have this capability, and now we have systems available to address these questions,” she adds.

5) The cells of the barrier have many specialized jobs.

Unlike most cells that divide to produce copies of themselves, epithelial cells differentiate and then die. These cells perform a variety of specialized functions to aid in absorption, secretion or formation of the mucus layer. But in patients with IBD, this differentiation process may be impaired.