Ever Wonder How Drugs

Get Their Names?

What’s in a name?

When it comes to naming drug products, the answer is rarely simple.

Just as all potential drugs go through rigorous safety assessments during their development, so do their names. That’s why a single name for a drug candidate can take years to get approval from regulatory authorities, in an entirely separate process from the approval of the drug, itself. The reason is simple: if a medication’s name is similar to another medication — either by the way it sounds or how it looks when written — the wrong product could get into a patient’s hands and potentially cause harm.

“The health authorities are constantly doing more to ensure the names they accept are safe to coexist with other pharmaceutical products,” says Michael Quinlan, who is a Senior Manager, Trademark Development, Market Research Insights, within the Global Commercial Analytics group with Pfizer. “We have hurdles that no other industry has because we put these inventions into our bodies.”

Specifically, every name must be distinct enough from other drug names to avoid confusion among patients, pharmacists and healthcare providers. That’s no easy feat, considering there are more than 20,000 prescription drug products approved for marketing in the U.S.1 And it explains why some medication names can feel so alien to the words we’re used to.

Want to peek behind the curtain and see how drugs are named? Read on.

It starts with a compound

When scientists discover a substance that holds promise to become a potential drug, they label the compound with a series of letters and numbers, which are then registered in an internal database for drug discovery.

Pfizer, for example, labels its compounds with the letter PF, for Pfizer, followed by up to 10 numbers: eight numbers are for the compound, followed by two additional numbers that represent the salt form of the compound if applicable so it might look PF-04965842-01. In the past, Pfizer’s compounds included just six digits. But over the years, after all eligible number combinations were exhausted, two additional numbers were added.

If the compound continues to show promise during early experiments and is advanced into clinical trials, and there are plans for potential commercialization as an approved innovative product, two distinct naming processes then begin: one for the potential drug's generic name, and one for its brand name.

How drugs get their generic names

When scientists discover that a potential drug that holds promise, the processes of developing the generic name and brand name begins. The United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council works in coordination with the World Health Organization's International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Programme to ensure global consistency. The generic name will allow the drug to be universally known, so that if a person is traveling abroad and needs a particular medication, they can inquire about the one they use back home and access it by the same name.

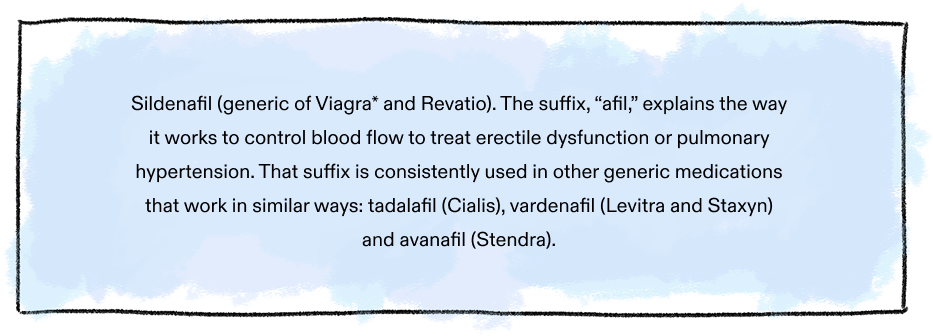

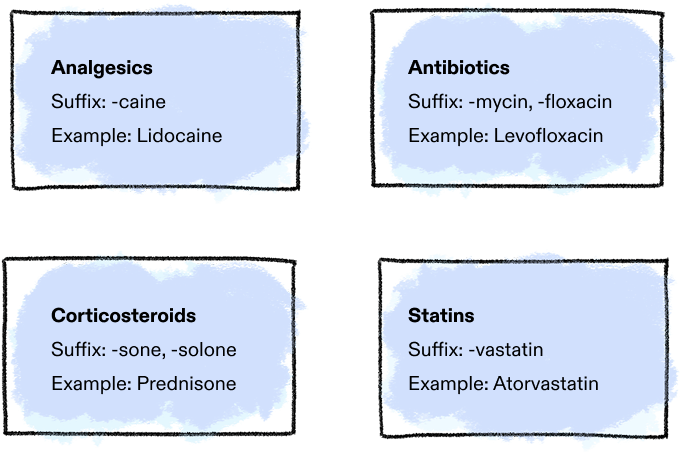

Generic drug names have two parts: a prefix and a suffix. The suffix acts as a scientific family name to describe the way the drug works in the body, while the prefix is often chosen to reflect the drug’s chemical structure or therapeutic class, as well as distinguishes the drug from other medications, and may impart a mood or a feeling. “We look for syllables that obviously are different from other existing generic names and that are pleasant enough in their tonality or appearance, so it doesn’t become overly complex to try to pronounce the generic name,” says Quinlan.

Common drug suffixes and examples:3

When the cross-functional team narrows it down to three to six names, it submits those names to the United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council, which may accept or decline the options. If all are declined, USAN may propose an alternative name, which the team can accept or decline and submit new names.

Once accepted, USAN submits the name to the World Health Organization (WHO) INN Programme. A committee reviews the name and accepts it or declines and offers an alternative. When a name is accepted by WHO, it’s published on a list the public can view and object to. If, after four months, no one objects – which is exceedingly rare – the name can officially be used.

A checklist for coming up with generic names for drugs:

YES

Does it use two syllables in the prefix? This helps distinguish the name from other existing names.

YES

Is it free of medical terminology? Many medications can be used to treat a variety of conditions, and you don’t want to limit your potential drug to one particular function.

YES

Is the prefix pleasant in its sounds and/or appearance? The way the name reads should be inviting and easy enough to pronounce.

NO

Is it similar to other existing generic names, or brand names, or drug company names? Avoid this to prevent potential confusion with other medications.

NO

Does it include the letters H, K, J W and/or Y? These letters aren’t used by some other Roman-based languages in their alphabets and generally should be avoided particularly for international naming, because the name of the potential drug can’t be communicated globally.

NO

Does it sound like marketing? The name shouldn’t resemble a company name, use words that exaggerate the benefits of the medication or sound promotional in any way.

How drugs get their brand names

Dreaming up the brand name of a drug allows for a lot of creative freedom. As the potential drug shows promise, a team must first decide what message or tone they want the name to impart. There are a lot of things to consider: should it have a strong-sounding name, or a gentle-sounding name? Should it be aspirational, or scientific? Is the team aiming for the name to resonate with consumers, or will its audience consist of healthcare providers? Those are just a few of the many questions they’ll ponder.

Then, the company developing the drug will frequently work with a pharmaceutical branding agency, which will devise a list of hundreds of potential names for the medication at hand. Pharmaceutical companies often conduct extensive trademark searches and linguistic analyses to ensure the name is appropriate globally. Coming up with those names is never simply about the drug of interest. The moniker must also be distinct enough from all other drugs, so that there’s no possibility of confusion. “If your name has more than 70% similarity to an existing drug name, it's probably not going to get approved,” says Quinlan. To help with the process, regulatory agencies, such as the FDA, publish guidance and build tech tools to assist in identifying potential similarities.

After conducting internal and external surveys and database searches, one name will rise to the top, and will be submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA's Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA) plays an important role in reviewing proposed brand names. If the FDA rejects the name, the drug maker will need to submit another and begin the process again. The FDA's Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (DMEPA) plays an important role in reviewing proposed brand names.

A checklist for coming up with brand names for drugs:

YES

Is the name unique? It’s essential that the name isn’t similar to other brand names or generic names and doesn’t infringe on any trademarks.

YES

Does the name pass muster outside of the U.S.? Drug products should be appealing on a global scale, and a linguistic check should confirm that it doesn’t sound like anything embarrassing or offensive in other languages.

YES

Has market research affirmed that the name is acceptable and memorable? Opinions from internal stakeholders, healthcare providers and consumers can offer valuable insights.

NO

Does it sound like marketing? The name shouldn’t sound like the company name, use words that exaggerate its benefits or sound promotional in any way.

NO

Does the brand name look or sound too much like the generic name? It must avoid any use of any generic name stems (like “afil”) to avoid confusion and should not be overly composed of too many letters from its own generic name to avoid rejection.

NO

Could the name be mistaken for another medication? There are several tests a name must undergo to affirm that it is unlikely to cause a medication dispensing error, including the way the name sounds when spoken, how it looks when it’s written (including in messy script), the dosage form and strength associated with the potential name, and its similarities to other names when listed in a drop-down digital menu for e-prescribing.

Brand name drugs and the inspiration behind them:

INLYTA:

An aspirational name that suggests

enlightening

LYRICA*:

A melodious name that calls to mind music and song lyrics

VIAGRA*:

A strong name that elicits similar words, such as vitality and vigor

IBRANCE:

A name meant to evoke comfort by conjuring notions of inspiration, embrace and vibrancy

*While speculative, the actual reasoning behind a name may be more complex or proprietary

Naming medications is both an art and a science. It’s a collaborative process that can involve dozens of experts and opinions and result in hundreds of ideas before arriving at a single name that’s accepted by authorities.

It’s laborious, complicated, time-consuming and thrilling. And, admittedly, the resulting label can sound a little bit strange. But there’s a reason for that: as more drugs are developed, it’s increasingly difficult to find a unique—and acceptable—name.

“It can seem like drug names are getting more complex, and that’s not intentional,” says Quinlan. “It’s just that there are so many approved names, and so many trademarks that are filed for names, that drug developers must be ever-more creative to come up with names that can safely and legally coexist. It’s a challenge, but it’s always worth the time and the effort because we’re putting patient safety first.”

References:

1 FDA Regulated Products and Facilities. FDA’s Office of the Commissioner. April 2023. Available at https://www.fda.gov/media/176816/download Accessed Nov. 4, 2024.

2 Generic Drugs: Questions and Answers. FDA. 3/16/2021. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers#q1. Accessed 11/5/2024.

3 Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN); Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, editors. Nursing Pharmacology [Internet]. 2nd edition. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College; 2023. Table 1.8, [Common Classes of Medications, Examples, Suffixes, and Roots]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK595006/table/ch1pharma.T.common_classes_of_medication/ Accessed 11/05/2024.

4 Brand name (drugs). Healthcare.gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/brand-name-drugs/ Accessed 11/5/2024.

* Lyrica® and Viagra® are registered trademarks of Viatris Specialty LLC.