Attacking Cancer Cells That Develop Resistance

By Get Science Staff - This article originally published on Get Science

When cancer patients receive therapy for an extended time, they often face the specter of drug resistance as tumor cells mutate and find ways to evade the cancer-killing medicines.

Exploring new ways to disarm rogue cells that have developed resistance is a major field of modern cancer research. One way to address the issue of resistance is to attack cancer through the fundamental processes that drive their core mission — to multiply unchecked and invade healthy organs.

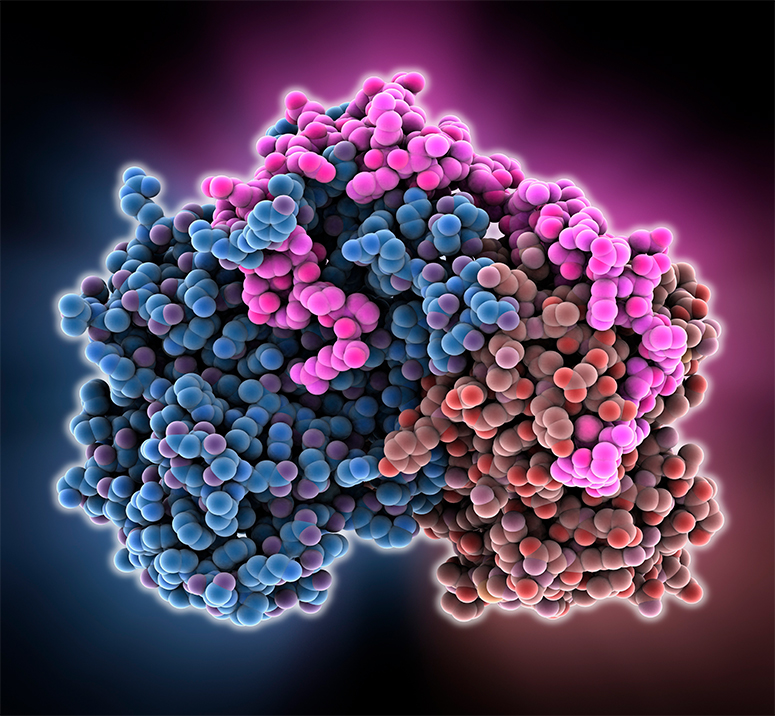

Unlike traditional chemotherapy, which essentially poisons the cancer cells, medicines called cell-cycle kinase inhibitors put the brakes on uncontrolled cancer cell proliferation by blocking only key enzymes that drive cell division.

Researchers have discovered that a class of kinase enzymes, the cyclin-dependent kinases, or CDKs, are commonly over-active in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Specific inhibition of certain CDKs in combination with anti-hormonal therapy is beneficial to this patient population, explains Dr. Stephen Dann, Senior Principal Scientist at Pfizer’s R&D site in La Jolla, California. “It's a very novel mechanism because instead of just shutting down a cancer gene, which is the mechanism used by a lot of targeted therapies, this kinase inhibitor actually reactivates a tumor suppressor.”

And using kinase inhibitors to mount a frontal assault on the machinery that drives cancer cell proliferation isn’t the end of the story. “While Pfizer does have an approved CDK inhibitor, cancers activate a different kinase to start growing again,” Dr. Dann says. When researchers discovered this was the case, they started working on strategies to address likely resistance.

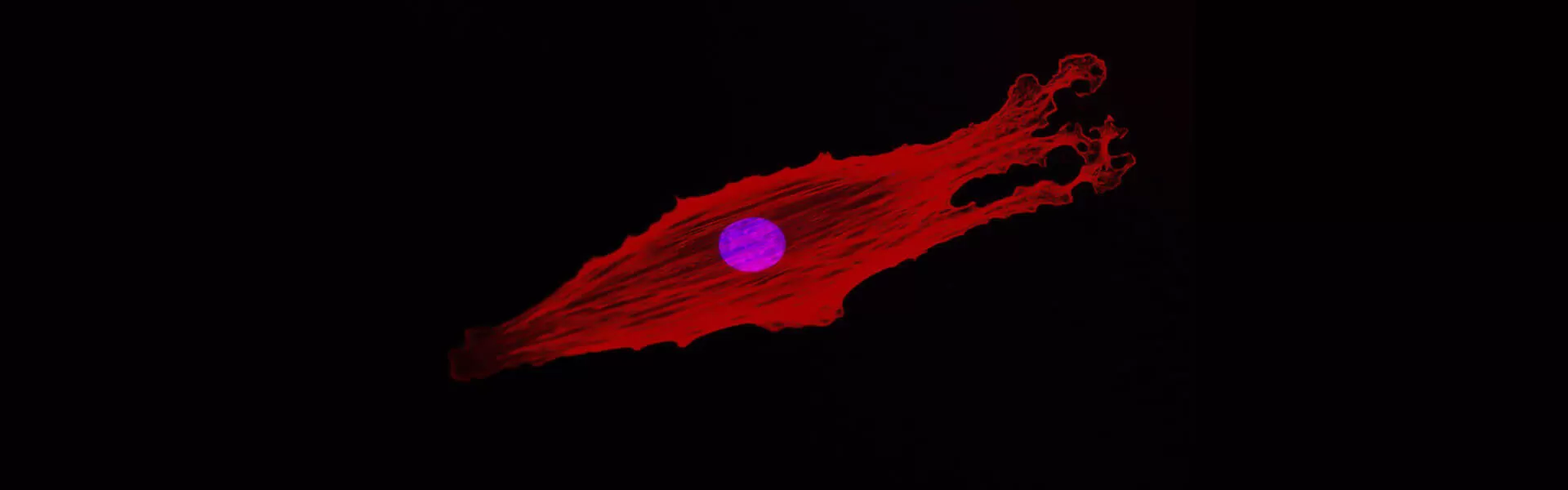

“Tumor cells are always trying to find loopholes,” he says. “So, my work is focused on determining those mechanisms of resistance. We’re trying to figure out ways that the disease gets around that kinase inhibitor,” Dr. Dann says. “It's like having a half-filled balloon—you squeeze on one side and it just pops out the other. That's what's happening in a tumor cell. You're getting a lot of very quick evolution where those cells that survive tend to be more and more aggressive.”

“When you're targeting a cancer gene, it's often a game of whack-a-mole, where you hit the cancer cell adaptation as it comes up,” Dr. Dann adds.

Recent research by Dr. Dann and his team in breast cancer has zeroed in on next-gen medicines that specifically target additional CDK enzymes. For reasons that are still being uncovered, these inhibitors show promise in addressing resistance to certain CDK inhibitors.

Targeting those specific types of CDK enzyme is like trying to “thread the needle,” he says, in that you’re trying to reactivate that tumor suppressor while at the same time suppressing the CDK enzymes to just the right degree to avoid toxic side-effects to healthy cells. “We’re hopeful that cancer cell adaptation to this class of compound is going to be difficult to achieve in patients.”

Early clinical trials for this new generation of kinase inhibitors are underway and could yield invaluable insights into approaches to control malignant disease and combat the issue of resistance.

![]()