The Long And Short Of Aging

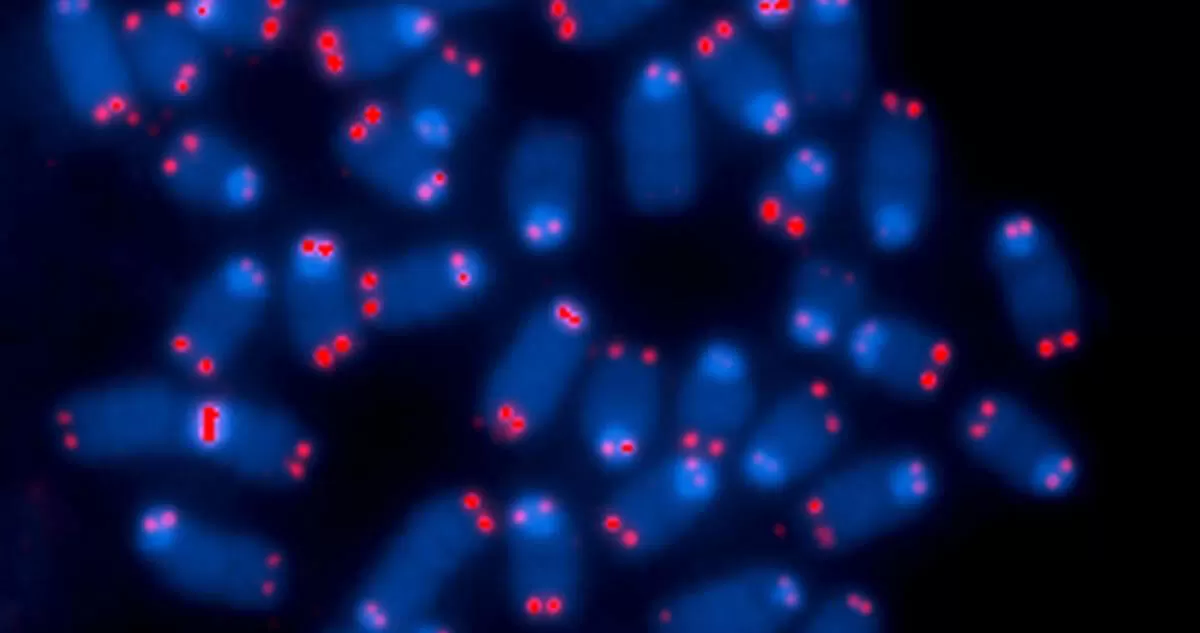

The length of our telomeres, the caps on the ends of chromosomes, can predict how well we’re aging.

If you’ve been sticking to your New Year’s resolutions to exercise more, eat healthier, and better manage stress, turns out that more than your waistline and well-being are benefitting. You may also be helping maintain your telomeres, the parts of chromosomes that affect aging.

Watching Telomeres

Telomeres are protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, often likened to the tips on the ends of shoelaces because they protect DNA from being damaged during the cellular replication process. Each time a cell divides — such as to grow new skin, blood, or bone — telomeres on the tips of chromosomes are slightly clipped off. As a cell divides through its lifespan, which may be about 50 to 70 times, the telomeres get shorter and shorter, until they reach a point where the cell dies. This is part of the natural aging process.

A growing body of research, however, shows that the length of our telomeres — and how cells age in general — may be associated with factors within our control, such as diet, sleep, exercise, and stress. In a new book The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer, molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn argues that our daily habits can impact the length of our telomeres and put us as at increased risk for disease. “Your telomeres, it turns out, are listening to you,” writes Blackburn in the introduction to her book. “They absorb the instructions you give them. The way you live can, in effect, tell your telomeres to speed up the process of cellular aging.”

Common sense lifestyle tips, such as getting seven hours of sleep a night, doing moderate exercise three times a week, and eating omega-3 fatty acids have been associated with decreases in telomere shortening, according to Blackburn. It’s still up for debate in the scientific community whether positive lifestyle factors can also reverse aging and lengthen damaged telomeres. On the flip slide, scientific evidence shows that negative lifestyle factors (such as stress, smoking, lack of exercise) is linked to greater telomere decline.

In 2009, Blackburn won the Nobel Prize for her research on telomeres, including the discovery of the enzyme telomerase that helps replenish these protective DNA caps. While the interaction between the enzyme and lifestyle changes is still up for debate, Blackburn was a part of a study in 2013 that found that men with early prostate cancer who adopted healthy habits had an uptick in telomerase activity and increase in telomere length.

There is still much research to be done in the field, but early data shows that we are not entirely resigned to our genetic destiny, and positive behaviors may benefit us down to our cells.